Every year, the NZ Companion Animal Register (NZCAR) helps reunite hundreds, if not thousands, of animals with the people who love them. When we looked back at the data from 2025, some clear patterns emerged — and they tell an important story about why microchipping and registration matter.

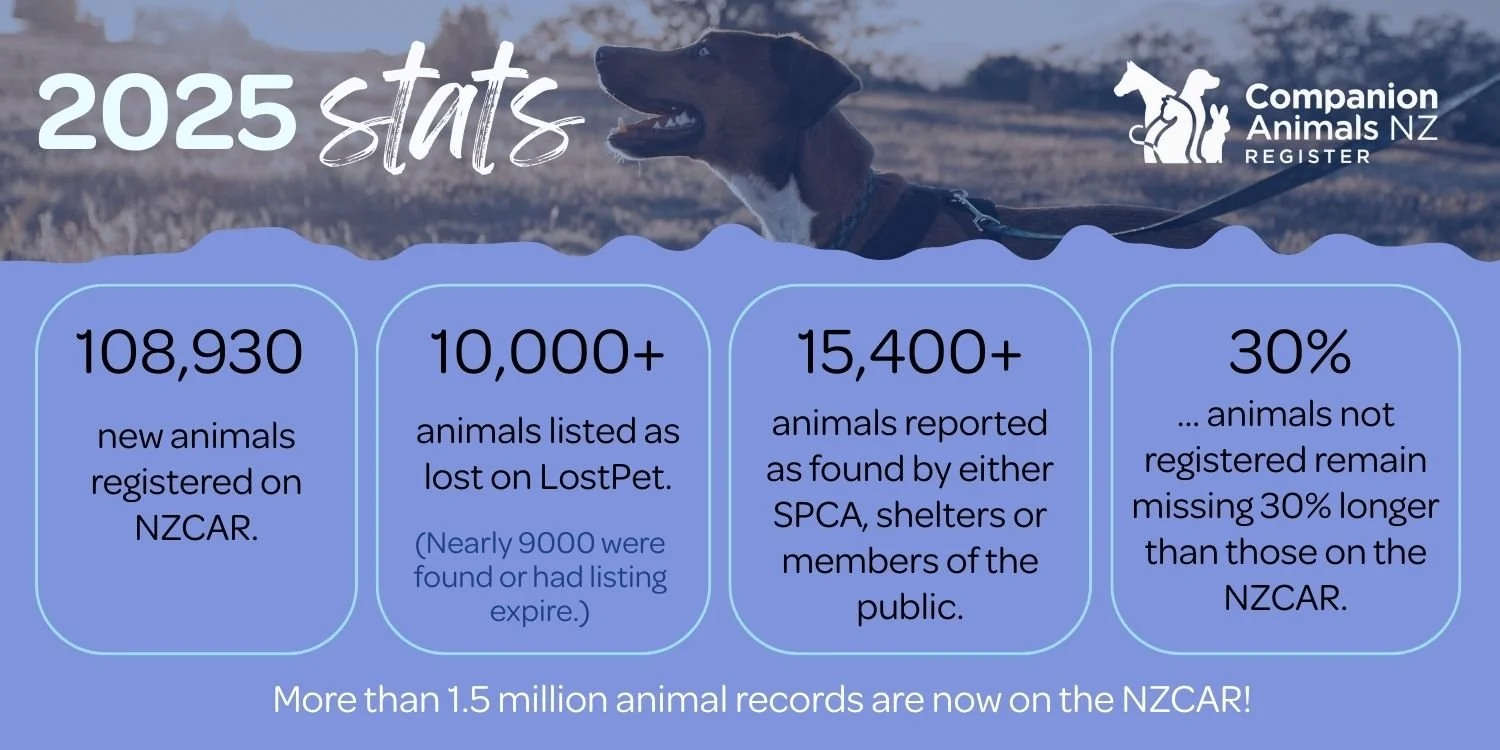

The numbers at a glance

108,930 animals were registered on NZCAR in 2025, helping ensure pets could be identified if they went missing. This brings the total animal records on the NZCAR to 1.5 million.

More than 10,000 pets were reported lost during the year on LostPet (Of these, nearly 9,000 were marked as found or listing expired).

Over 15,400 animals were reported as found by either SPCA, shelters or members of the public trying to identify their guardian or get them home safely.

The number of dogs reported lost increased by nearly 10% compared with the previous year, highlighting the ongoing importance of prevention and identification.

What the data tells us:

Time matters. The longer a pet is missing, the more likely it is that a microchip and up-to-date registration will be what ultimately brings them home.

Registration makes a real difference. Animals that are not registered remain missing around 30% longer than those registered on NZCAR.

Some species are especially vulnerable. Excluding cats and dogs, fewer than 20% of other animals reported lost on LostPet are microchipped, making reunification much harder.

Cats tend to be missing for longer. Cats are more likely to roam and may be taken in by well-meaning people, or simply go unidentified — which is why microchipping and registration are so important for cats.

Based on our available records (from October 2023 onwards), December 2025 had the highest number of 'found’ pet listings to date (animals marked as ‘found’ by members of the public trying to identify their guardian or return them home). Summer is definitely when there are more lost and found listings, and we are also seeing an uptake in people using the platform.

“ “Every day, Approved Users reunite pets with their families all across the country - often without our team ever knowing, which is a sign the system is working. ”

“NZCAR works thanks to the combined efforts of our Approved Users and our support office,” says Sarah Clements, NZCAR Manager. “Every day, Approved Users reunite pets with their families all across the country - often without our team ever knowing, which is a sign the system is working. At the same time, our support office supports people through some of their hardest moments, hearing the distress and worry that comes with a missing beloved animal.

“We’re incredibly grateful for both, and we always appreciate hearing your success stories. Do reach out if you've had success being reunited with your animal as a result of their NZCAR registration as it is a great way to give people in similar situations some well-needed hope!”

The takeaway

These insights reinforce a simple but powerful message: microchipping and keeping registration details up to date gives lost animals the best chance of getting home — especially when time passes.